Why didn't she come forward before now?

/I hear it again and again and again.

Why the allegations now?

Why didn’t she say she was raped back when it happened?

How can we believe her, especially when her name isn’t even public?

My rapes were very real. My rapist lives free. No charges were ever filed. I tried to tell some adults in my life, but they didn’t want to hear it.

And? For the past couple of decades, I’ve tried to pretend what happened to me didn’t matter, doesn’t matter. But it did. And it does.

Even if the allegations are never voiced, they bubble up in other ways. Perfectionism. Promiscuity. Alcoholism. Depression. Repeated abusive relationships. Self injury. Drug abuse. Suicide attempts. You see, the pain has to go somewhere.

And healing? Healing from sexual assault is a lot like a prolonged version of pouring hydrogen peroxide on a wound. Sure, it cleans out the dirt and debris and other unhealthy gunk, but it hurts like hell in the process. And it doesn’t mean a scar won’t be left behind.

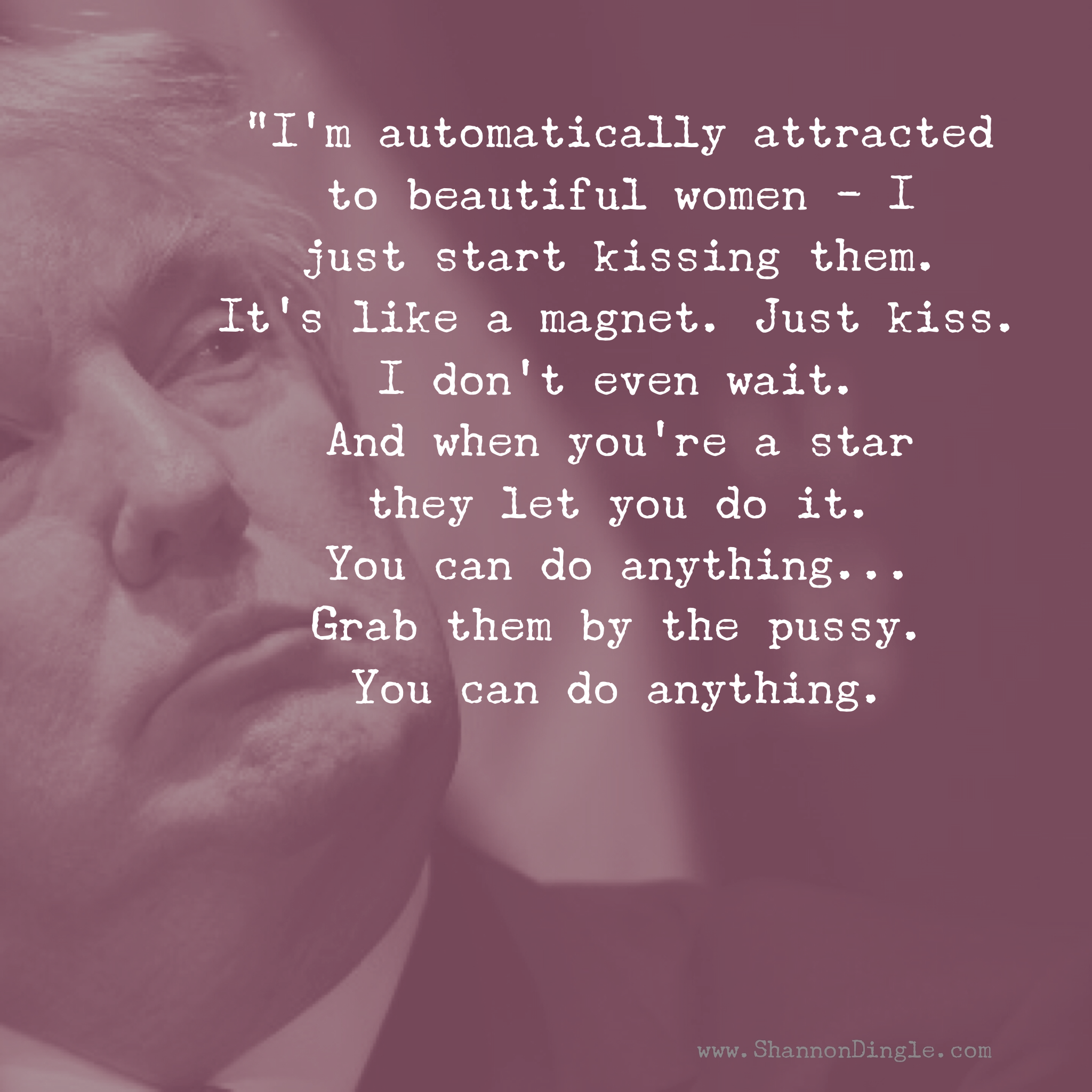

I posted about a rape allegation against a presidential candidate yesterday, and the chorus of accusation-questioning and victim-blaming began. (I’ve been following this case for months, but I didn’t post about it until now because I couldn’t bear to read these sorts of comments.)

Why didn’t she come forward sooner?

Doesn’t this seem opportunistic?

Who is paying her to say these things?

When someone accuses another of robbery, we don’t see these questions. We don’t ask what they were wearing, why they were hanging out with the types of people who rob others, if they said no clearly… no, we understand that it’s a violation when someone steals someone else’s wallet.

But when a man violates the body of a woman, all of a sudden her credibility is the primary concern.

When I was in elementary school and a boy from my speech therapy group grabbed my hand and put it on his crotch? I was told I shouldn’t have been on the corner of the playground where adults couldn’t see well, the implication that my location stripped me of the right to be safe from sexual harassment.

When I was in sixth grade and a boy on my bus rubbed his hand on my rear or between my legs as I walked by? I was told I needed to sit closer to the front of the bus so he wouldn’t be tempted, the implication that I somehow asked for the attention as I walked by.

When I was in eighth grade and was caught kissing my boyfriend in the schoolyard after the final bell? The teacher lectured me about how I should have known better without saying a word to the boy, the implication that boys will be boys but girls have to be better.

When I was in high school and went to my friends’ youth group? I heard lessons on sexual purity about how guys are visual creatures so it’s the responsibility of young ladies not to be teases who lead them on, the implication that if anything happened sexually – with or without consent – the girl was to blame.

And those lessons don’t include the words said to me by an adult when she found out about the first time I was molested: “Things like this don’t happen to good girls.”

And those lessons don’t include what I learned with each rape: “Your body can be taken from you at any moment.”

These lessons, they’re taught young. They make up rape culture. And they don’t even include the comments we read about victims, the questions about credibility, the way they’re put on trial as much as the offender. This misplaced blame grows into something more insidious: shame.

Truth says what happened to you was disgusting. Shame says you’re disgusting because of what happened to you.

Truth says this is one part of your life story. Shame says this defines your life story.

Truth says even when trauma was caused in the context of a relationship, healing is found in relationship too. Shame says no one can ever know what happened and still love you.

Truth says the offender did a bad thing. Shame says you, as the victim, are a bad thing.

Why don’t women come forward earlier? Because speaking this truth is hard, and because shame runs deep. Because investigations include invasive exams that are often retraumatizing. Because sharing the details of what happened to me with my husband and therapist is hard enough, but doing so with officers and lawyers and other strangers makes me want to throw up. Because justice might be no jail time at all or such a measly sentence that it feels like a whole ‘nother assault. Because sexual predators often seek out kids and adults who lack the internal and external supports to fight back, both during the assault and afterward.

Fighting shame and speaking truth requires others. We can’t do it alone. My people – my husband and those close friends who believe me and believe in me – are God’s ambassadors to my hurting heart when I’m swallowed by the pain of my past. But everyone doesn’t have people like mine. And that’s part of why every victim doesn’t become a survivor. Suicide, overdose, homicide, and so on… that’s the end of too many of our stories, far more statistically than the general population.

So why didn't she come forward before now? I don't know her exact reasons. I do know mine. But, honestly, I think we should all be amazed – given our culture – that any victims ever come forward instead of questioning those who do.