Why the outrage now? And what can we do next?

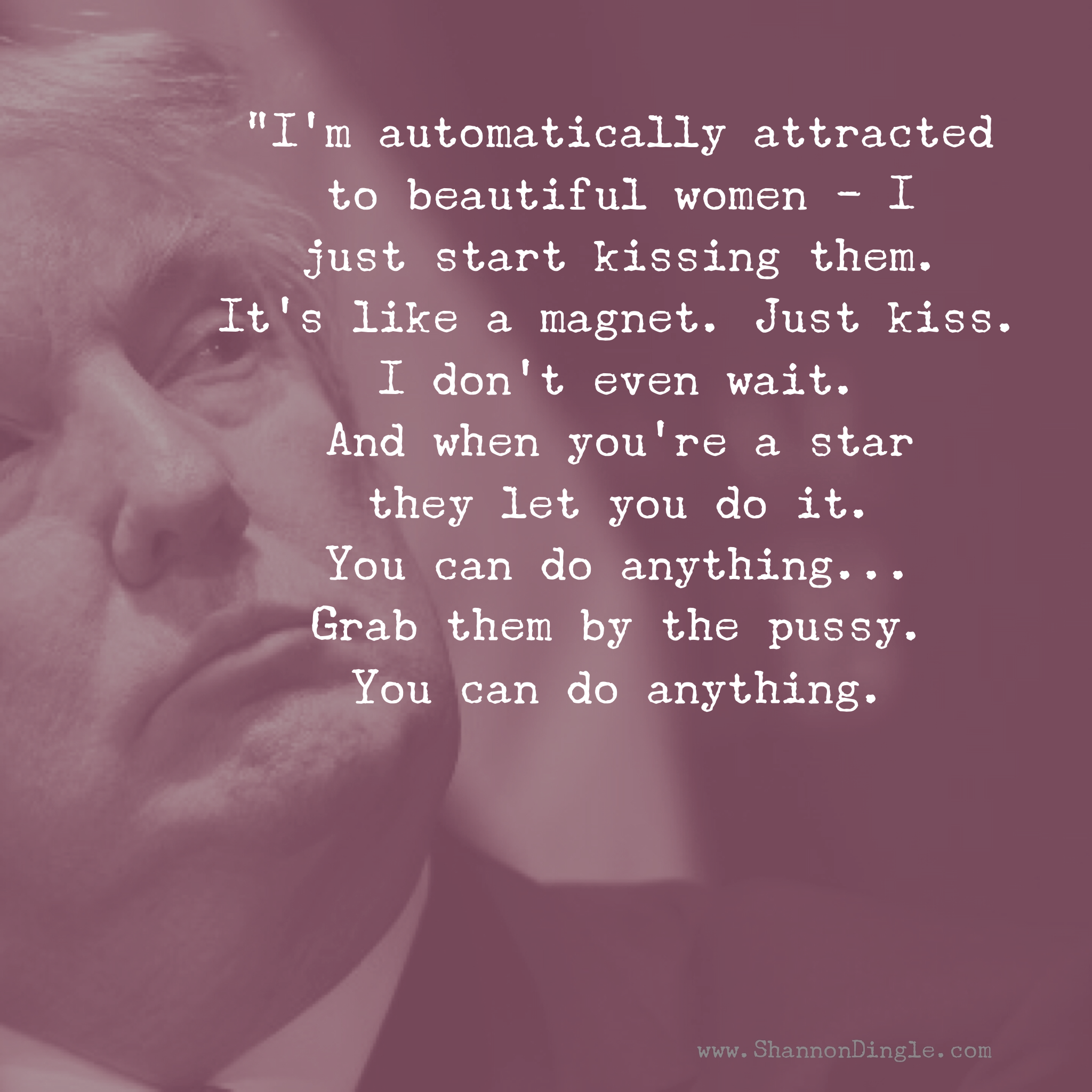

/By now, you’ve heard Trump’s latest scandal. His words led me to make the image below and post it – along with my personal story of sexual assault – on Facebook. And then I took a Xanax, because his words plus my own PTSD created a physiological anxiety that couldn’t be quelled without pharmaceutical help.

That post been shared thousands of times now, and I’ve had to ban nearly 100 people from my author page for horribly disrespectful comments, most in defense of Trump. Let me repeat that: After I shared a painfully vulnerable history, a variety of Trump supporters chose to argue against my experience and, in a couple dozen of those comments, personally insult me.

I’m not shocked, though I wish I were. But I am confused, not by the comments but by the newly found outrage about Trump’s most recently released misogyny. Where was this before now?

Trump has said other terrible things about women, both in recent news breaks and older stories. In fact, a rape case against Trump – with a 13 year old victim – goes to court in December. So why the new outrage now? Why are the numbers rising of Republicans and Christians denouncing him?

I’m thankful for the Christians who had already said no way to Trump. I signed this statement. I said no to him from the beginning. I stand by that. I still do. (And I think it’s noteworthy that the signatories on that statement are more diverse on many counts, including gender and race, than those often seen in evangelical leadership, but I’ll get to more on that in a moment.)

This week Beth Moore spoke out. I thanked her. Russell Moore continued to speak out. I thanked him again, having done so in person previously. Others are joining them, while some – like Franklin Graham and James Dobson and Eric Metaxas – have sunk in their heels. (I’ll gladly update this post if any of those back down; Metaxas has deleted his initial tweet dismissing the latest scandalous words from the candidate he’s endorsed, so I'm hopeful.)

And then Wayne Grudem, who endorsed Trump as the moral choice for president, took back those words. He admitted,

“Some may criticize me for not discovering this material earlier, and I think they are right. I did not take the time to investigate earlier allegations in detail, and I now wish I had done so. If I had read or heard some of these materials earlier, I would not have written as positively as I did about Donald Trump.”

I am thankful Grudem has withdrawn his support. I’m even more thankful that he admitted he should have done more research before his prior endorsement. He could have retreated from his previous stance with less humility than that.

But? Many sound responses to Grudem’s piece existed well before this week. (The seven I’m linking here are just a few.) Grudem had the opportunity to right his wrong. And he didn’t. Not until now. Why? I’m glad we’re finally collectively saying, “That’s enough,” but why wait so long, after evangelical support for Trump has already tarnished our reputation?

Why is this our breaking point?

Here’s the main difference I see: now the people targeted by Trump's words have my fair skin. These Christian leaders look like me or my husband. In other words, they’re white. They keep talking about their wives or sisters or daughters, who are also white. Now that white women are being debased with his verbal abuse, we relate. We care. We empathize.

In other words, this time we consider the victims of his hate speech and his sexual assaults to be our neighbors, because they look like us. (And, yes, sexual assaults. That is, after all, what his words described.)

Those who he’s previously insulted and verbally defiled – Mexicans and other Latinos. People of color. Those with disabilities. Muslims. Refugees. – don’t look like us or our daughters, sisters, wives, and mothers. And so? Because we’ve defined them as the other, we don’t relate. We don’t care, not in such a personal way. We don’t empathize. We simply change the channel or say, “but abortion…” as if these other lives don’t matter to us too.

In other words, those other times we didn’t consider the victims of his hate speech and his verbal assaults to be our neighbors, because they aren’t like us.

“Who is my neighbor?” a lawyer asked Christ in an exchange recorded in Luke 10.

Jesus didn’t answer that his neighbor is his mother or wife or daughter or sister. No, Jesus offers a story of an injured man on the side of the road, a brutalized victim belonging to a group considered to be different and other and less than and dirty. The priest wouldn’t touch him because doing so would have made him unclean and would have required a return to the temple to cleanse himself. He couldn’t be bothered. Likewise, the Levite passed by.

Then the Samaritan showed up – surprising the audience listening to Jesus (as Samaritans were generally despised by Jews and vice versa) – and became the unlikely hero. He showed compassion, backed it up with action and money, and set a model for us all. And Jesus said to the lawyer, “Go and do likewise.”

I’m glad we’re finally noticing Trump’s hateful words. But I wish we had cared enough for those who aren’t white women to notice it before. I wish we hadn’t disavowed black people, those with disabilities, Muslims, refugees, and so many more as our neighbors by withholding our outrage until now.

In other words, I wish we had all acted a little more like the Good Samaritan and a lot more like Christ.

Take heart, though. There’s still time. We have failed to love God with our whole hearts and love our neighbors as ourselves, but let this be the moment when the Spirit convicts us to confess and repent from our sins.

Let today be the day that we all start listening to the pain of our neighbors.

(All of them, and not just the ones who look like me.)

Let today be the day when we pledge our allegiance to the kingdom of God rather than to any political party.

Let today be the day we heed Christ’s words.

Let today be the day we go and do likewise.

Amen.